Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

from Carolyn JonesCalMatters

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Subscribe to your newsletters.

This article is also available in English. Read it here.

In recent years, California has focused on primers, 1-2-3s and wheels on the bus, investing more than $5 billion in early childhood education.

But kindergarten, a staple of elementary schools for more than a century, remains optional. Despite nearly half a dozen legislative attempts to make it mandatory, California is one of 32 states that does not require all 5-year-olds to attend school.

That could change in 2026. Lawmakers plan to introduce a new bill to require preschool education and are confident it will fare better than its predecessors, which failed in committee or were vetoed, largely because of their cost.

“Kids need to be around other kids, they need to learn. That’s important,” said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California, an early childhood education advocacy organization. “I don’t see why California can’t do it.”

The data, according to activists, They are strong. Children who attend kindergarten have better math and reading scores starting in third grade and higher high school graduation rates. They are also less likely to be suspended or drop out later.

While California requires all school districts to offer kindergarten, it does not force families to enroll their children. Most do, but approximately 5% annually choose not to enroll their children. The reasons are varied: some families believe that children are not prepared for the rigors of school, while others are satisfied with their child’s current situation, whether it is in preschool, kindergarten or staying at home with the family.

Latin American families are less likely to send their children to kindergarten, the data show. Lozano explained that this is due to various reasons: either they don’t know it because of the language barrier; or are afraid to enroll their children in school because of immigration issues; or the parents are working so much that they have not received notices from the school district; or a combination of the three. In any case, schools need to improve their outreach with that community, he said.

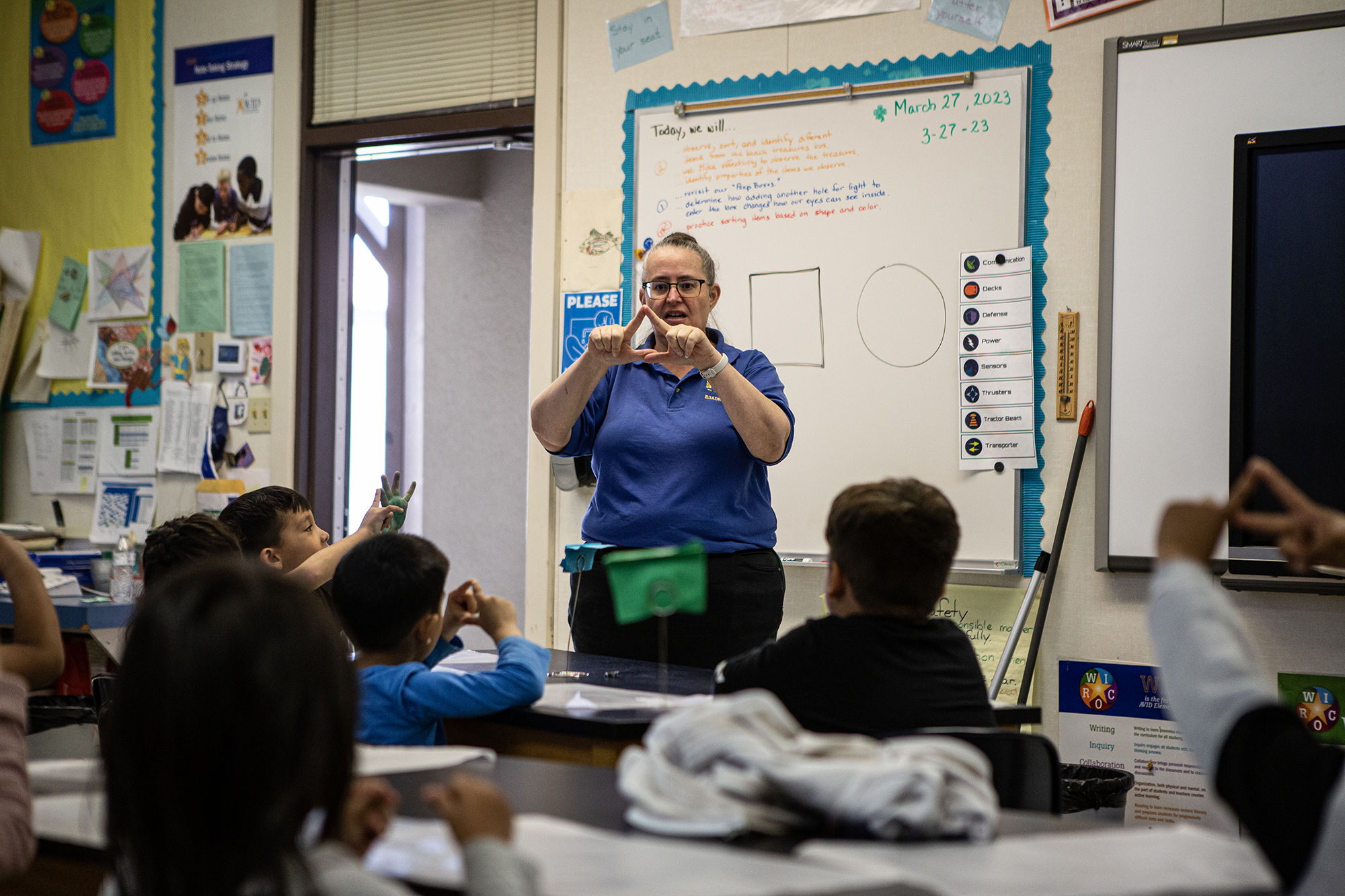

Cecilia Keys, a bilingual kindergarten teacher for the Sacramento City Unified School District, said she recently had a student whose mother was deported and the child was unable to attend school because there was no one to take her. Although she loved school and the family highly valued education, it was logistically impossible to get her to school. It took several weeks for the school and family to arrange transportation.

“For Latinos, education is fundamental. We want to give our children the best we can,” said Kiss, who is also the mother of a kindergartner. “But sometimes we can’t do everything. We rely on caring teachers to care for our children, help them learn and prepare them for first grade.”

State Senator Susan Rubio stated that the fact that kindergarten is not compulsory discourages already disadvantaged families from enrolling their children. In their experience, Latino families have great respect for the public school system, and if it tells them that kindergarten is optional and therefore not a priority, “they listen.”

That’s why he proposed two previous bills to make kindergarten compulsory. The state needs to send families a clear message: Early childhood education is essential to students’ academic and personal success, he said. The state of California now there is a transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds, expanded state-funded preschool and added more spots to its subsidized day care program. The next step should be to strengthen the kindergarten, he added.

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tony Thurmond, agrees with this assessment. This month, he announced that kindergarten is compulsory This is a legislative priority until 2026 and has pledged to support any bill that affects him. Several lawmakers said they would consider sponsoring one.

Two previous Rubio kindergarten bills failed: a in the Senate Appropriations Committee and the other when Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed it. In his veto memo, he said he supports early education in general, but that the state has not budgeted for the cost, estimated at $268 million a year.

“While the author’s intention is laudable … it is important to maintain discipline when it comes to spending, especially current expenses,” Newsom wrote.

Numerous groups supported the bills, including the California Teachers Association (the state’s largest teachers union) and several school districts. However, there were some opponents, notably the California Home Education Association. The group’s opposition was not based on the benefits of kindergarten itself, but on the state’s ability to disenfranchise parents.

“Most kids are already in kindergarten. But some parents have good reasons to keep their kids at home,” said Jamie Heston, a member of the group’s board of directors. “Parents want to have the choice to decide what’s best for their children.”

The Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association has not commented on the issue, but is generally opposed to new initiatives that cost money, such as compulsory preschool. That position is unlikely to change if the early childhood education bill comes up again, the group’s vice-president Susan Shelley said this week.

“From a budget perspective, there’s a lot of pressure this year to keep spending under control,” Shelley said. “This will not be a one-time expense. It will be ongoing. And there is no urgent need for kindergarten expansion compared to other more pressing needs facing the state right now.”

Bruce Fuller, a professor of education at UC Berkeley and an early childhood education specialist, said the Legislature needs to focus on the most pressing needs of children under the age of 6. These include how the introduction of transitional kindergarten has led to the closure of many preschools, leaving many 3-year-olds without daily care. In addition, Head Start faces financial difficulties and other obstacles imposed by the Trump administration, including attempts to exclude non-citizen families. And even though California has expanded access to state-funded preschool, not enough families know they’re eligible.

“There aren’t that many families giving up daycare, so it’s not a huge need,” Fuller said. “There are more immediate concerns.”

Still, Rubio is confident the kindergarten bill has a good chance of passing this year, in large part because the Legislature has experience significant turnover since it last voted on a preschool education bill in 2024. Twenty-seven new senators and assembly members were elected last fall.

For Rubio, whose parents immigrated from Mexico, the issue is personal. Although she did well in school, her twin brother did not. He was mistakenly assigned to special education at an early age, fell behind and struggled throughout his school years, eventually dropping out. Rubio believes he would have been better off if he had received a high-quality early childhood education.

She is also an elementary school teacher and has seen the difference between students who have attended preschool, traditional kindergarten, and kindergarten and those who have never enrolled in school until first grade. Children who have attended kindergarten know how to hold a pencil, write their names, count to 20, wait their turn and maybe even read or do basic math, she said. Those who didn’t attend fell far behind their peers, and some never caught up, he added.

“I have very vivid memories of my students breaking down in tears at the end of the year because they couldn’t take a test. They didn’t know the answers and it’s very painful to watch,” said Rubio, who is on leave from her job as a teacher in the Monrovia Unified School District in Los Angeles County. “It’s hard for them and for the teachers because these kids need a lot of extra help.”

Lozano said he believes the bill will eventually pass. The initiative will cost money, but the state will save money in the long run if more students succeed in school and graduate.

“It took us 20 years to get TK. It takes time to change opinion and policy,” Lozano said. “Kindergarten offers so many benefits, especially for the children who need it most. We believe the benefits outweigh the costs.”

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under license Creative Commons Attribution/Attribution-Noncommercial.